A Mild Epiphany about the Balls

in two memories

Epiphanies are these tiny phenomena of the mind; the distant sound that makes you ask, “What was that?” or the streak of light that brushes against your vision. They bridge the unrealized and human experience. They are largely underexplored.

When you are imprisoned in a person’s mind, as I am, sitting in the childhood living room of Happy Julius Pipe (the human whose mind I’m in), you notice his epiphanies. You note them, meditatively, and if you’re not too intoxicated, you say aloud (to the extent you can be audible in a person’s mind):

“Happy. Epiphany. Drink!”

This is Kuf, formerly from Xobtihs, bringing you another plate of garbage from the mind of Happy Julius Pipe. I have collected a few snippets over the last few weeks and turned them into a story, all while monitoring the electrical anomalies of his brain farts.

We are in the year 2025. Happy sits at the dock on the lake, watching his children grow older. R1 is doing flips off the lake trampoline. In a few years, he will be an adult. He won’t need to ask Happy questions; he won’t approach him with the same curiosity as he did when he was nine. Happy remembers R1 when he was nine.

How much they change in a few short years. A glowing pink jellyfish dances across the forefront of Happy’s mind. Epiphany?

Happy has been having frequent, almost casual, epiphanies on the dock, much like the moment when a person walks and trips over an uneven sidewalk. He stumbles, but he doesn’t fall, and says to himself, if only to be more careful, “that was a close one.” Happy’s epiphanies are like that, far from miraculous and not uncommon.

And yet, images flicker and Happy remembers a moment in time not that long ago…

He and Renetta share a master bathroom, which should be for them exclusively, but the kids are always using it. The kids have their bathroom, but prefer their parents' shower because it has better water pressure and more jets.

Happy remembers shaving, enjoying two seconds of quiet, when R1, his then nine-year-old, storms into the bathroom, steals the shower, and begins his inquisition.

Peace is ephemeral for the middle-aged father.

R1 has a very determined look in his eyes.

——

And now, here is the first memory. I’ll get to the second one later.

“Dad,” Happy hears R1 calling him. “Dad?”

“Can you give me a minute?” Happy asks. (I believe this is a common question that parents ask their children when they want them to go away. Children then ignore it.) Any hope of luxuriating in his shave has come and gone.

Happy is suddenly fearful. R1 wants to talk. (Narrator’s note - on Xobtish, I never had to explain anything and rarely had to converse with another Xobtishian. But on Earth, human life is one talk after another. And even though I am imprisoned in Happy Julius Pipe’s memories and emotional baggage, there are elements of this life that still feel surreal. Kids fall into that category. Children are either wired incorrectly or prone to malfunction. For example, Happy can never get their attention when he wants it, and he cannot avoid their demands when he needs to. It's as if whatever behavior he requires of them to maintain parental sanity, they do the opposite.)

“Hey, Dad?” R1 asks. He is most persistent. R1 believes that he can get whatever he wants as long as he keeps addressing his father. He knows that Happy will relent eventually. R1 is masterful at disregarding his father’s social cues, and as such, he crosses the boundaries of Happy’s personal space effortlessly.

In this situation, feeling the general frustration of wanting to shave but knowing that he might never be alone again, Happy sinks deeply into the storehouse of his mind to find all acceptable responses.

R1 asks the question: “What do your balls do?” This is the first time one of his children has asked him about the balls. Naturally, he is not prepared and falls back on the most clinical answer possible.

“They are essential for human reproduction,” Happy says, hoping this will satisfy R1’s curiosity and stop this line of questioning.

“Do you put it in the hole?” R1 asks. This is Happy’s fault. If his children were self-sufficient and had a baseline awareness of social norms, he wouldn’t be challenged this way. As a consequence, he must resort to using a word he never dreamt of using in front of his nine-year-old son.

“Er, vagina,” he says. “Animals reproduce sexually, which involves both male and female sex organs.”

“So you stick your balls in the hole?” R1 is unrelenting with the balls.

“Again, the balls are essential,” Happy says. “But the part that goes in the hole, I mean, vagina, is the penis.”

The wheels are turning. Happy admires his son when he can see him thinking, reconciling his understanding of life’s mysteries. There it is: the great and powerful sex, capturing the best and worst of the human imagination since the dawn of self-awareness. And this conversation, if Happy is capable of managing it, may navigate R1 to an appropriate level of sexual well-being. (Happy is incapable of managing it; however, and we all know that the best he can offer is uncomfortable blather.)

“That sounds terrible,” R1 says. Why would anyone do that?”

“A fair question. You cannot have children unless you engage”. In fairness, Happy never thought about having the birds and bees conversation, especially at this age. At least it can’t get any worse.

“How old do you have to be to use the balls?”

“Marriage age,” Happy says, somewhat ashamed. “That is, when you have the money.”

“So if you are not married, you don’t use your balls?”

“There are many permutations. Nonetheless, the math involved is complicated,” Happy says.

“Wait, I need math to use the balls?”

“No, what I mean to say is that ball usage is a hard optimization problem for people who study such things, especially as it relates to marriage. What you need to remember is this: when you are ready to use your balls, be responsible.”

“Like when I am old enough to get a dog?”

Is it possible to confuse a child more? “Look. What you need to remember is that the balls are essential and you must use them responsibly. And you don’t need math.”

R1 realizes that he should have gone to his mother with this question.

“I’m done talking about this,” he says and runs off.

Thank God! Happy can feel his insides compress as he connects this scene with another memory.

——

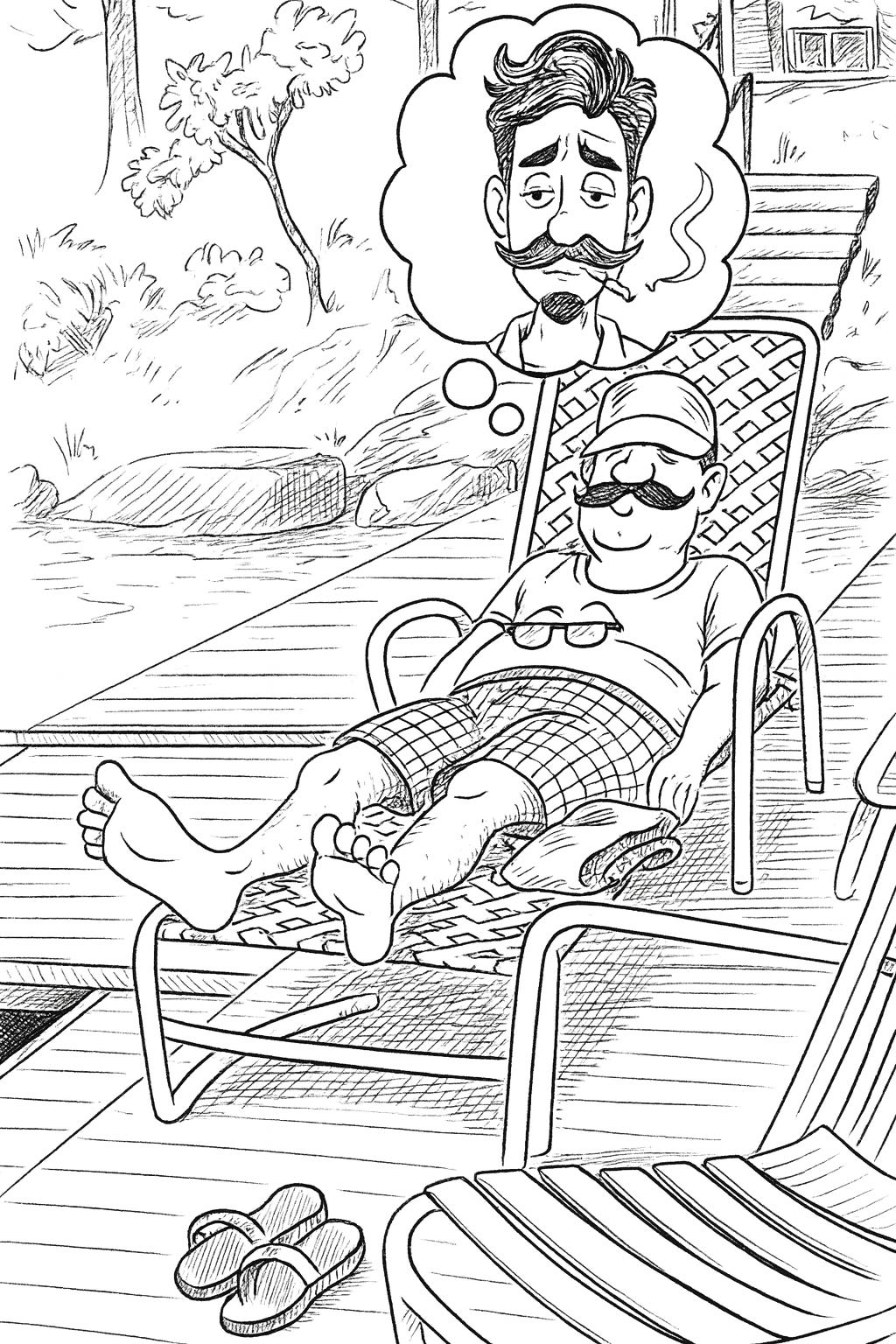

We return to Happy back on the dock, floating in the current moment. The kids are diving and jumping off the lake trampoline. Happy is merely forty-seven and capable of mild jumping, but these activities become more challenging with age. To jump on the trampoline, he must swim over to it, pull himself up on the floating platform, then pull himself up onto the trampoline and jump. It sounds straightforward, but the last time Happy attempted a jump was a few weeks after his failed birds and bees talk. He was forty-four. Exactly three years earlier. How does Happy remember this?

He nearly broke his balls —flashback to the connecting memory.

——

The year is 2022. Happy is standing on the dock watching the children jump in the lake.

The lake trampoline comes with a slide and a log attachment that connects to part of the trampoline. The log attachment serves no purpose except to make the trampoline more phallic. It moves when you walk or jump on it, and no human has the requisite balance to make it to the end of the log. R1 flies through the air. He tries to balance himself on the log, but fails and falls into the lake. It is amusing to watch. All the children try to balance themselves and walk across the log, but fall into the lake.

There are 5 to 7 other children in total, including Happy’s kids: R1 and R2. They play the game to see who can be the first one to make it to the end of the log. Five to seven children try and fail with uproarious laughter. Their resiliance inspires Happy, and after watching them lose their balance several times, he concludes that he can balance himself on the trampoline log.

For one thing, he is a man with an older, heavier, and inflexible body. If he is honest with myself, he is more likely to jump the width of the lake than touch his toes, a fact that should deter him from leaping off a trampoline and landing on the log attachment. But then again, Happy is a man. And as a man, he possesses a primordial idiocy that runs counter to his general character.

So he swims over to the trampoline, pulls himself up, and balances on the side of the trampoline. He bounces a few times, then informs the children and the other adults on the dock that he, Happy Julies Pipe, will jump and balance himself on the log.

Happy can easily visualize this: the jump, the landing.

But what comes next is pain; the kind of pain that a middle-aged man will suffer if he jumps off a water trampoline onto a log attachment. And it’s not just his balls that hurt. The entirety of his groin, all of it, crushes against this granite inflatable log. He wants to howl a good old “Shit! Fuck!” but holds back. There are children present.

“I’m okay,” he whispers as he doggie-paddles to the dock. He manages to pull myself up the ladder and eases into one of the Adirondack chairs. R1 is there. The wheels are turning in his head.

“That wasn’t very responsible,” R1 says. He shows the perfect balance of concern and devious laughter. On the one hand, his father may have broken his balls, but on the other, nothing could be funnier than watching a grown man attempt something so catastrophic.

“I’m okay,” Happy says, grimacing. He is in severe pain.

“You’re lucky you're married,” he says. “Or you might never use your balls again.”

Happy can’t articulate what he might have taught his son about the balls. Whatever it was, his actions spoke more loudly than his words. His actions hurt even louder.

——

This is how human shitbags make memories and form connections: they sit on a dock and remember their failures.

For Happy, this is relatively easy.

Happy looks at R1. He can see the nine-year-old and twelve-year-old versions overlap in perfect juxtaposition. The twelve-year-old looks so much older and taller than the nine-year-old. It’s hard to believe that he is the same person who, three years earlier, was asking about the balls.

R1 emerges from the lake. Five to seven children are on the trampoline.

“If you ever need to talk about anything, I’m here,” Happy says to R1.

“Like what?” R1 has no idea how his father’s comment is relevant to the current situation.

“Like any questions you might have or feelings you don’t understand.”

“Did you see how much air I got on my last dive?” R1 asks.

“Quite impressive”, Happy says. And just like that, the morning fades and Happy sinks into the day, floating on the dock one memory at a time. Don’t worry. He did not attempt another jump.

And his balls, despite their age, remain intact.

-Kuf out

Stay tuned for the next installment of Alien Idiom by subscribing to my free newsletter. I pop one off around the end of every month in the hopes that other humans might read it. Mostly, they don’t.